Dr. Aron Szulman talks about his father, Jakub Szulman (1889-1942)

17 July 2014

Interview about Jakub Szulman

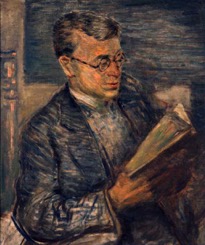

Interview about Jakub SzulmanIn this statement, Dr. Aron Szulman talks in English and then in Polish about Lejzerowicz’s drawing of his father, Jakub Szulman, the lay director of Ghetto Hospital #2 (Drewnowska / Holzstrasse 75). Jakub Szulman, born in Kremenchuk, central Ukraine in 1889, left that part of the Russian Empire for the Polish lands before World War I. Szulman was a socially committed journalist, Zionist, and community leader. Growing up in Kremenchuk, his family spoke Russian and Yiddish; he learned Polish after he moved to Poland. Jakub Szulman came to Łódź following the lead of his sister, who had studied at the school for midwives in Warsaw and got a job in Łódź. Jakub Szulman was a person of significance in Łódź, especially in the Jewish community. In addition to his other accomplishments, Szulman was a founding member in 1925 of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research (Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut), then based in Wilno, Poland (now Vilnius, Lithuania). Lejzerowicz made this drawing of Jakub Szulman on paper in 1940; it is preserved in the Jewish Historical Institute’s art collection in Warsaw (A-888/20). The inscription on the drawing reads: “Panu J. Szulmanowi w dowód serdecznej przyjaźni” (to Mr. J. Szulman as a proof of sincere friendship).

Jakub Szulman’s death in January 1942 came as the result of a heart condition. In a notice about Szulman’s death, the ghetto chroniclers give a sense of the man’s character and his importance in the community:

“On January 2, Jakub Szulman, aged 52, well-known in Jewish society as a socially active and indefatigable civil leader in Łódź’s Jewish life, departed this world in the prime of his life. Szulman, of blessed memory, enjoyed the same trust and universal respect in the ghetto as he had in pre-war Łódź. Until the last moments of his life he held the important position of chief of Hospital No. 2 on Drewnowska Street. Due to his uncommon abilities and selfless perseverance, the deceased distinguished himself in organizing life in the ghetto, which earned him the fullest appreciation of the ghetto’s leader and of everyone who worked along with him. Among other things, the ghetto owes the creation of the building superintendents’ system and successes in the field of hospital management to the initiative of the decreased. Szulman, of blessed memory, was one of those rare people of whom all, without exception, can speak only in superlatives. Ghetto society has lost an extremely useful, righteous, and noble man of great merit. . . . Hundreds of people from all walks of life, as well as Chairman Rumkowski, took part in the funeral ceremony. The deceased is survived by his wife and son.”

[The Chronicle of the Łódź Ghetto 1941-1944, edited by Lucjan Dobroszycki, translated by Richard Lourie and others, New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1984, pp. 109-110; this section of the chronicle was originally written in Polish.]

After anti-Semitism prevented him from being admitted to study medicine in Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine), Aron Szulman left Poland in 1938 to study in England, first at Harrogate (Yorkshire), then medicine at the University of Birmingham. He was one of several young Polish-Jewish men from Łódź who went to England to study. Szulman’s wife Irene is a survivor of the ghetto of Łódź, having lived at Bazarna 1 during the ghetto period, close to Lejzerowicz’s studio at Rybna 14A; she did not know the artist. The couple met in Boston after the war and make their home in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where this interview was recorded in July 2014. (3:17)

I am sorry to report that Dr. Aron Szulman passed away on 22 November 2014.

A "new" self-portrait published in 1927

20 August 2013

Yesterday, art historian Irmina Gadowska (Łódź) discovered a previously unknown self-portrait by Lejzerowicz that was published in a pictorial supplement to the Freie Presse, a German-language newspaper in Łódź on 29 January 1927. Although the quality of the reproduction is only fair from the digitized newspaper, we see a portrait of the painter reminiscent of the style of Lucas Cranach or Albrecht Dürer with a second oval-shaped face as a kind of shadow on the left side of the painting. Could the oval face be a reference to the famous character of Maria in Fritz Lang’s expressionist masterpiece film Metropolis, which dates from the same years (production 1925-1926)? This would go along with other Lejzerowicz paintings that show the impact of German expressionist art of the 1920s.

Ruth Lewis talks about her drawing

13 August 2013

Ruth Lewis on drawing

Ruth Lewis on drawingIn this recording, Ruth Lewis, formerly Ruth Leiserowitz, talks about her memories of being drawn by her uncle, Izrael Lejzerowicz, during a week that she spent in Łódź in the mid-1930s. Ruth was born in Berlin; her father was the artist’s brother, Samuel Leiserowitz. Thanks to Samuel, Ruth, and her children, a number of original artworks as well as numerous photographs of the Lejzerowicz/Leiserowitz family have survived.

Ruth had met her uncle earlier in her life, when the painter stayed with the family in Berlin in the 1920s. During the week that Ruth and her mother spent in Łódź, the painter was persuaded to draw a sketch of the 13-year-old girl. In this recording, made in her home in August 2013, Ruth talks about that experience.

Meyer Rozenblum (ca. 1900-1942)

23 July 2013

Left: Courtesy Magnes Collection, University of California; gift of Ephraim Margolin.

Right: 1938 photograph courtesy Nelly Levin, Tel Aviv, Israel

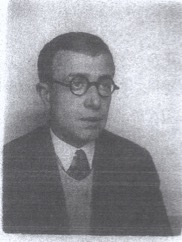

An interesting portrait of the scholar and teacher Meyer Rozenblum by Lejzerowicz can be found in the University of California’s Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life in Berkeley. Rozenblum - called “Blum” by some of his young students in the 1930s - scratched out a meager living by teaching and tutoring. An avid chess player and Yiddish-language poet, Rozenblum was first and foremost a scholar. He was a friend of the Margolin family and belonged to their circle, having gone to school with the writer Julius Margolin. This may explain why the Margolin-Spektor family commissioned his portrait in the 1930s. In one of his books, Julius Margolin remembered Rozenblum with great affection, even though he and his friends criticized him for his passivity: “He was a complete being, faithful to his principles, incapable of compromise, hypocrisy, or lies, a free being who refused to let himself be regimented. He couldn’t belong to any party and no need would have made him accept working in an office: it would have been in contradiction with his profound self. Notwithstanding his absolutely carefree attitude, his lack of energy and ambition that was revolting to his friends, he was one of those gentle obstinate people who live by their own lights, who don’t allow themselves to be manipulated, one of those people who are the most untamed in their day-to-day humanity. . . . He led a difficult life. His activities as a teacher seemed to anguish him and to revolt him; he showed a total lack of interest in his students. But in spite of that, an atmosphere of sympathy and friendship, which he didn’t in any way foster, surrounded him. It was enough for him to just be himself: a man of an absolute independence of spirit who stood for a kind of authentically Jewish fanaticism and Innerlichkeit [introspective nature]. He annoyed us, we criticized him, . . . but we couldn’t do without him.”

Margolin reports that, having escaped from Łódź to Pinsk on the Soviet side of the border created after the German and Soviet invasions of Poland in September 1939, Rozenblum eventually decided to accept a Soviet passport and took a job in May 1940 as a French teacher in a lyceum in Krzemieniec (now Kremenets, Ukraine). After the German invasion of the Soviet Union, he was murdered along with the other Jews in Kremenets in August-September 1942.

[Julius Margolin, Voyage au pays des Ze-Ka. Traduction du russe par Nina Berberova et Mina Journot, révisée et complétée par Luba Jurgenson. Paris : Le Bruit du Temps, 2010, p. 88. English translation from the French translation: William Gilcher, July 2013.]

Shṿeln and other literary journals of the 1920s

11 July 2013

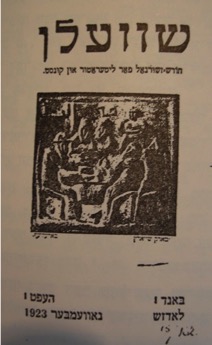

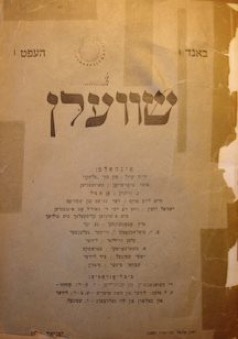

Left, cover of November 1923 issue of Shveln from an illustration at YIVO, New York. Right side: cover of 1924 issue, courtesy Library of Congress, African and Middle Eastern Division, PJ5120 .A359

Lejzerowicz reportedly submitted drawings to newspapers and literary journals in Łódź in the 1920s. These covers come from issues of Shveln (which means “Threshholds”) dated 1923 and 1924. The cover on the left features an illustration by the artist Marek Szwarc, originally from Zgiersk, a town just north of Łódź, who was by then living in Paris. Alas, only the cover seems to have survived.

The issue on the right survives at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, but contains no illustrations - and also no poetry or other work by Lejzerowicz. Perhaps additional issues have survived in other collections. If anyone knows of their whereabouts, please let us know!

The literary critic Chaim Leib Fox gives the following list of Yiddish-language publications to which Lejzerowicz submitted work:

1922-23: Toyz Royt / טויז רויט

1923: Vegn / וועגן

1924-25: Shveln / שוועלן

1924-25 der fraytik / דער פֿרײַטיק

1923-1939 nayer volksblat / נײַער פֿאָלקסבלאַט

Late 1920s: lodzher togeblat / לאָדזשער טאָגעבלאַט

1926-27: ekstrablat / עקסטראַבלאַט